Issue 2: Voice

A quarterly conversation about process and craft with authors Anna-Marie McLemore, Emily X.R. Pan, Anica Mrose Rissi, Sara Ryan, and Nova Ren Suma.

Welcome back to The Eavesdrop, with Anna-Marie McLemore, Emily X.R. Pan, Anica Mrose Rissi, Sara Ryan, and Nova Ren Suma. In this issue, we’re discussing voice—what even is it? How do we decide what type of voice is right for a story? How do we troubleshoot when the voice isn’t working?

Pull up a chair. We’re glad you’re here.

And don’t miss this season’s extras—including a giveaway for subscribers—at the end.

Sara: I’ve been thinking a lot about voice lately. I’m working on a historical YA, and finding the right voice for this book feels like a different kind of craft challenge than finding the voice for a contemporary novel, because the voice needs to feel both evocative of the historical era and accessible and engaging for present-day readers.

So I’d love to talk about how we define and understand voice, and also how we approach crafting the voice(s) in our work. I think for me, voice is kind of an amalgam of style and POV; on the style side, voice involves things like word choice, sentence structure and length, and pacing, and on the POV side, the choices are about determining the lens or lenses through which readers will experience the story. How do you all think about voice?

A-M: When you talk about lenses, that’s really the heart of it for me, and that touches everything else. The lens or lenses the character(s) bring to their own world and experiences impacts word choice, sentence structure and length, pacing, narrative distance. Even if you have a character who sets out to be as objective and straightforward as possible, they still bring their own filters to the narrative. And then with the reader experience, you have another layer, because we as readers bring our own lenses, which is part of the magic of reading, that a book is, in a sense, a new book with every reader. There’s also this tension in reading and observing voice, how we can get close to characters, but we also have enough distance to be able to ask: what do these characters carry with them as they encounter the world?

Emily: Yes to all of this. There’s the narrative voice and then there are the voices of each individual character, and sometimes that overlaps if, say, you’re writing in first person. But I absolutely agree that the lens of a character must inform their voice, and some of that comes out in the cadence and rhythm of the sentences, but it also comes out in the way they think. Does a character do a lot of stream-of-consciousness type ruminating, vs. does a character try to avoid thinking out of maybe some fear, vs. does a character have the tendency to speak all their thoughts out loud and interrupt people as they do so—all of this contributes to their voice. If the story is narrated in third person then does that narrator editorialize and offer commentary that’s separate from the characters? Is it an omniscient presence who renders certain judgments as the story is being told? There’s a lot about voice that’s very instinctive…but there’s just as much that’s technical and specific.

Nova: All of what’s been said so far pinpoints what voice is for me. Voice is the first thing I think about when I approach the writing of a new book. The choice in voice (or voices, if there are two or more narrators) and the perspective that reveals itself through that voice is what determines all my plot decisions from there. At first I’m asking myself questions like: Who is this character and what do they know—or don’t know, or can’t know? Where do they come from and where are they now? From what point in time are they telling this story—looking back from a specific moment, or in the midst of the experience? Who are they telling this story to? What are they hiding, from the reader and from themselves? As I consider these questions, details like tense, word choice, flow, and rhythm get clearer on the page and the voice takes shape. I often think about what one of my first editors told me fifteen years ago when we were talking about all the revisions that were awaiting me for my debut YA novel (spoiler: many, many revisions were awaiting me). She said that when deciding to acquire a book, if she falls for something that has a strong voice but a weak plot, she’s far more inclined to make an offer than she would if it was a strong plot but a weak voice. "Plot can be fixed," she told me. "Voice—you either have it or you don’t." With that in mind, I am always reaching toward making my narrative voice shine.

Anica: That’s interesting to think about. In my editor days, I looked for projects where I connected strongly with the voice, but I didn’t consider voice unfixable. In fact, helping a writer strengthen and refine not only the voices of the characters but also the voice of the novel could be even more satisfying than helping them figure out the plot. (You’ve all defined voice beautifully already, so I’ll add only that I think of a book’s voice as akin to its personality: as essential to what it is—and as difficult to fully describe or capture by parsing individual elements—as a human’s personality might be.) There needed to be something about the voice that sparked and held my interest, but through deliberate attention to the many style and craft elements listed above, voice can shift in both subtle and dramatic ways. By now, editor Gordon Lish’s influence on Raymond Carver’s voice is the stuff of legend. And I’m sure all of us have discussed voice with our MFA students as a series of not only instinctual but also deliberate choices that an author makes—and, therefore, can change.

I’m like you, Nova, in that finding the voice of the novel (or essay or picture book) early in the process is essential for moving forward, because so much of what the book will become emerges from that voice. But I’m also the kind of writer who revises constantly as she goes, and a lot of that revision is related to voice. I’m always playing with other ways to say things, and assessing the impact of various choices on the moment and the whole. Voice is something I feel my way into, then analyze and adjust obsessively.

A-M: So when you talk about analyzing and adjusting the voice, what is your approach when the voice isn’t clicking? How do you go about troubleshooting the voice in a work, and how does this change for you from story to story?

Emily: I love the idea of it being troubleshooting. I wish I had a faster way to go about it, but for me this requires a lot of experimenting. I start with instinct first. I’ll write whole chapters in one narrative mode, experimenting with one voice, and then rewrite the same chapters in a different narrative mode, watching and waiting for a specific style and sound to emerge, and seeing how I like it. I have to do a lot of this feeling around, like I’m blindfolded and groping for a direction, before I can start doing it on purpose. Once I have even a few paragraphs that capture what I like, then I start trying to do it intentionally, and I ask myself a lot of the questions you all have mentioned above, like what my character is hiding and who they really are. Sometimes I also pause to examine the feel of the overall story. I ask myself how the style impacts pacing and such. For the book I’m currently working on, I started out writing it as third person present tense, and I liked how that allowed me to play with language and ideas. But I realized I wanted more immediacy in the story. I wanted to be constrained by what I could see and feel and learn in the head of my main character, speaking through her voice. And so in my latest rewrite (which is quite the overhaul, and not your typical revision) I’ve switched to first person present tense.

Nova: I adore that vision of you groping around for direction, Emily, feeling your way toward something you can’t yet fathom. When it comes to troubleshooting, I often discover that the problem I was working to solve isn’t the problem I thought it was. For me, when the voice is wrong, that may be an indication something else is wrong: the character. Maybe I’m forcing my character to do something that isn’t organic to the story just because I want it there. Most likely I haven’t fully explored the motivations and core emotions and experiences that make up who this character is—which, in turn, shapes the voice on the page. Sometimes I’ve chosen the wrong character to give a voice to entirely. When I was writing my most recent novel, Wake the Wild Creatures, there were originally two protagonists and two voices. I spent a long time troubleshooting the voices only to discover that, in fact, the story needed only one protagonist so she can go through a lasting change. What I thought were two different girls’ voices turned into one girl speaking from different points in her life. Now there’s her voice in the present, and her voice from the past. For a very long time I just didn’t know the character well enough to see what was needed to make the story click for me.

Anica: Usually by the time I’ve felt my way through the first third of a manuscript, the voice is close to what I want it to be. But with my forthcoming novel, Girl Reflected in Knife, I had the unusual and thrilling experience of making dramatic changes in a late-stage revision. I was already many years—and multiple drafts—into the novel, so I knew the narrator and her story very well. In earlier stages of drafting, that tends to be my focus: who is this character, what is her story, what does it need, and what do I need in order to tell it. But in revisions, I eventually get to the point where I can focus more on what the reader needs, and in discussions with my editor about what kind of reading experience I wanted Girl Reflected in Knife to be—short, sharp, addictive, and unsettling—my understanding of the possibilities around voice opened up, and I went back in to experiment further.

First, I cut about 12,000 words of thinking and explaining. Voice-wise, this holds the reader at more of a distance while also pulling them in closer: inviting them to pick up the breadcrumbs the narrator drops and discover the path on their own. (It also, I hope, makes the reader feel trusted.) Second, I did something truly weird with the tenses, which follow the story’s own internal logic instead of following the expected rules of narration. This element of the voice is unsettling because it’s unstable—much like the main character, who is experiencing a psychotic break. My goal is for it to feel like the book knows exactly what it is and what it’s doing, even when the reader does not. My fear is that my deliberate artistic choices will read as a series of errors. (The book comes out in April if you’d like to judge for yourself.)

A-M: Anica, I got a vicarious thrill when you talked about cutting 12,000 words. I really enjoy cutting words, and often it’s what helps me get at the voice. What’s the core of the voice when I pare it back? If I pare it way back, what’s left? That tells me a lot about what’s key to this character’s voice in this story. And this is a lot of why, when I work with writers who are having trouble with voice in a particular story, I encourage them to let their writing be expansive and voluminous, because first in giving themselves that space and then in pruning the words back, they can find pieces that are essential to how a character speaks or how a narrative sounds.

Sara: Wow, everyone, all your brilliant insights and process reflections are exactly why I wanted to ask this question! Anica, I love the framing of voice as a book’s personality, and also the idea of how honing the voice connects to the type of reading experience you want the book to provide. In my past work, I’ve focused strongly on developing characters and settings, and have sort of felt my way into voice based on the relationship between them. But y’all have made me realize that with my work in progress, I want to think more consciously about voice and the reading experience. I want the book to feel a bit like it could have been written in the 1930s, and I think this will primarily come from word choices, sentence structure and era-appropriate slang. But I also want readers to fall in love with the people, places, and situations, even though everything is taking place at nearly a century’s remove from today’s reader. So maybe I want the voice of the book to be akin to an alluring contemporary person who’s wearing a really cool vintage outfit??? I’m still figuring it out!

Emily: Ooh, I love that, Sara! It makes me think of Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo, which is set in San Francisco in the 1950s. Malinda definitely did the kind of work you’re describing with word choice and era-appropriate slang.

Sara: I recently saw Naomi Kritzer posting on Bluesky about how K.J. Charles writes queer romances with happy endings that take place in deeply repressive historical eras, and “pulls this off without anyone sounding like they parachuted in from 21st century Tumblr.” I’m not writing a romance per se, but I’d also like to pull that off!

Which makes me think about another aspect of voice: the extent to which it reflects or resists dominant-culture sensibilities. To come back to the idea of lenses, it’s a truism that historical novels are as much about the time in which they’re being written as they are about the time in which they take place. So you always have to navigate both your understanding of the conventional values and expectations of the era you’re writing about—the historical lens—and of the values and expectations of the present day, the contemporary lens. And then you’re layering your characters’ values and beliefs on top of that.

Come to think of it, I’d say this is also true when you’re writing secondary world fantasy; when you’re inventing cultures, you need to consider how much your characters buy into what their culture expects them to do and be, and that will influence both their individual voices and the overall narrative voice.

Nova: That is brilliant. And this speaks to science fiction and glimpses of the future too. Voice and worldbuilding can be intertwined if you make a clear-eyed choice about using the voice as a tool in this way. I think about how the world itself is brought to life through the limited lens of a first-person voice in a book like Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro, which is narrated by an Artificial Friend and so our understanding of the world can only ever be what this narrator deduces. The more limited a voice is, sometimes the more I see and understand about everything else.

Sara: Or maybe we’re always dealing with multiple lenses when we craft and experience narrative voice(s)? A-M was talking above about how each reader brings their own lens, and how “a book is, in a sense, a new book with every reader.” That makes me curious about the types of narrative voices that we find especially compelling as readers, which also inevitably influence our voices as writers. One author’s voice I come back to over and over is Tove Jansson’s—or rather, Tove Jansson’s as filtered through the translation of Thomas Teal, since I can’t read Swedish. I think of Jansson’s prose as astringent; bright and clear like sun on new snow. Here’s the first sentence of Fair Play: “Jonna had a happy habit of waking each morning as if to a new life, which stretched before her straight through to evening, clean, untouched, rarely shadowed by yesterday’s worries and mistakes.” What are some other voices you all have found compelling and inspiring?

Anica: When I think of novels in which the voice is central, I think of Vladimir Nabokov and Toni Morrison. Theirs are the rare novels where, years after most details of plot, setting, or character have faded from memory, my experience of the voice remains vivid. Each of their books is so fully itself, which is a goal I’ve started more consciously applying to my own work.

Emily: Ooh yes, great examples. Karen Russell always comes to mind for me too. And thinking towards the younger age categories, Jason Reynolds is another author whose various voices stick in my brain long after I’ve finished reading.

Nova: Sometimes there’s a voice that upends everything for me. A voice that turns me upside down in the best way possible, inspiring me but also challenging me as a writer. Just a few startling books that have done this in years past: Watch Over Me by Nina LaCour, and the way the voice reveals the narrator’s trauma through spare moments and the peeling back of layers until the core is revealed. The Seas by Samantha Hunt, and the way fantasy and reality merge through the voice until we’re not sure if the narrator is truly a mermaid or immersed in her own isolation and pain. And, if we’re being honest, The Astonishing Color of After by our own Emily, and the way the narrator’s emotional state is revealed through an artist’s eye for color, how we can see grief and, ultimately, healing manifest on the page. The first voice that ever struck me was the narrator in Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys—fragmented, stark, spare—which I read as a college student. At first I simply wanted to write like her. Then I came to realize that what I admired was the way the book is the voice, and I needed to find my own.

Sara: I recently rediscovered a strategy I heard about from Will Alexander, whose latest book, Sunward, is a delightful space opera about parenting robotic children. If you’re feeling stuck, instead of trying to write the story itself, write about the story, as though it already exists in an ideal form and you’re telling it to a friend. That can be a way into a first draft as well as a way to start approaching the voice. Also, sometimes when you’re trying to find the voice, the counterintuitive way to discover it is to mimic someone else’s, in part because it forces you to identify what exactly is compelling to you about the voice you’re mimicking.

Nova: Finding a character’s voice can sometimes feel like a hazy and overly esoteric task, but maybe some of us are thinking too hard about it. I know I can get locked up in my own head and then mired in the mud of the page. So here is some advice from Ursula K. Le Guin, when it comes to stretching yourself with a character’s voice:

Writers may need conscious practice in writing in voices that aren’t their own; they may even resist it.

Memoirists may write in only one voice, their own. But if all the people in the memoir say only what the author wants them to say, all we hear is the author speaking — an interminable, unconvincing monologue. Some fiction writers do the same thing. They use their characters as mouthpieces for what they want to say or hear. And so you get the story where everybody talks alike and the characters are nothing but little megaphones for the author.

What’s needed in this case is conscious and serious practice in hearing, and using, and being used by, other people’s voices.

Instead of talking, let other people talk through you.

. . . Listen. Just be quiet, and listen. Let the character talk. Don’t censor, don’t control. Listen and write.

Don’t be afraid of doing this. After all, you are in control. These characters are entirely dependent on you. You made them up. Let the poor fictive creatures have their say — you can hit Delete any time you like.

—Ursula K. Le Guin, from Steering the Craft

Anica: As one year ends and another begins, take note and take stock of this moment in your creative life. What worked well for you in 2025? What fed your creative energy, enabled progress and breakthroughs, or led to joy and discovery? What will you take with you into 2026, and what might you tuck away for a while or give yourself permission to let go of and leave behind?

I’m a fan of writerly pep talks, refrains, and reminders-to-self. What are the words you need to hear in order to flourish and persevere as you chase your creative dreams in the year ahead? Write them. Repeat them. Believe them.

Each quarter Emily will offer a Tarot reading to capture the energy we might carry with us through the season and into the next stage of our projects.

Emily: Ah, the Eight of Cups. In the iconic Smith-Waite deck this card shows a figure walking away from the cups, which are stacked in such a way as to look incomplete, like something is missing. But here, in this image from The Fountain deck, I like to think that the figure is staring into the distance, meditating upon the possibilities, holding the eight cups in their mind's eye. Either way, this card marks a potential turning point that requires some courage.

Let's consider whatever project(s) you might be wrestling with at the moment. If there's a story that you can't seem to get right—especially if you've been chipping away at it for a long time—this card might be gently suggesting that you take a break. Turn away, but know that it's just for the time being. Stick it in a drawer and get some distance. You can always come back to it, and if you do so after writing something else you'll be that much stronger and sharper of a writer, and might find it much easier to spot the solution that's long evaded you. For now, push yourself to write something new.

Alternatively, it might be worth journaling about your current project(s). In my personal practice I do a lot of stream-of-consciousness thinking out on the page about my novels, and it literally always unlocks something for me. Ask yourself: What do you think the story is lacking? How might you or your emotions (fear? high hopes and expectations? obstinacy?) be getting in your own way? What's feeling boring, or where are you encountering resistance? Why? And then maybe challenge yourself with this one: Can you experiment with writing it from a completely different angle?

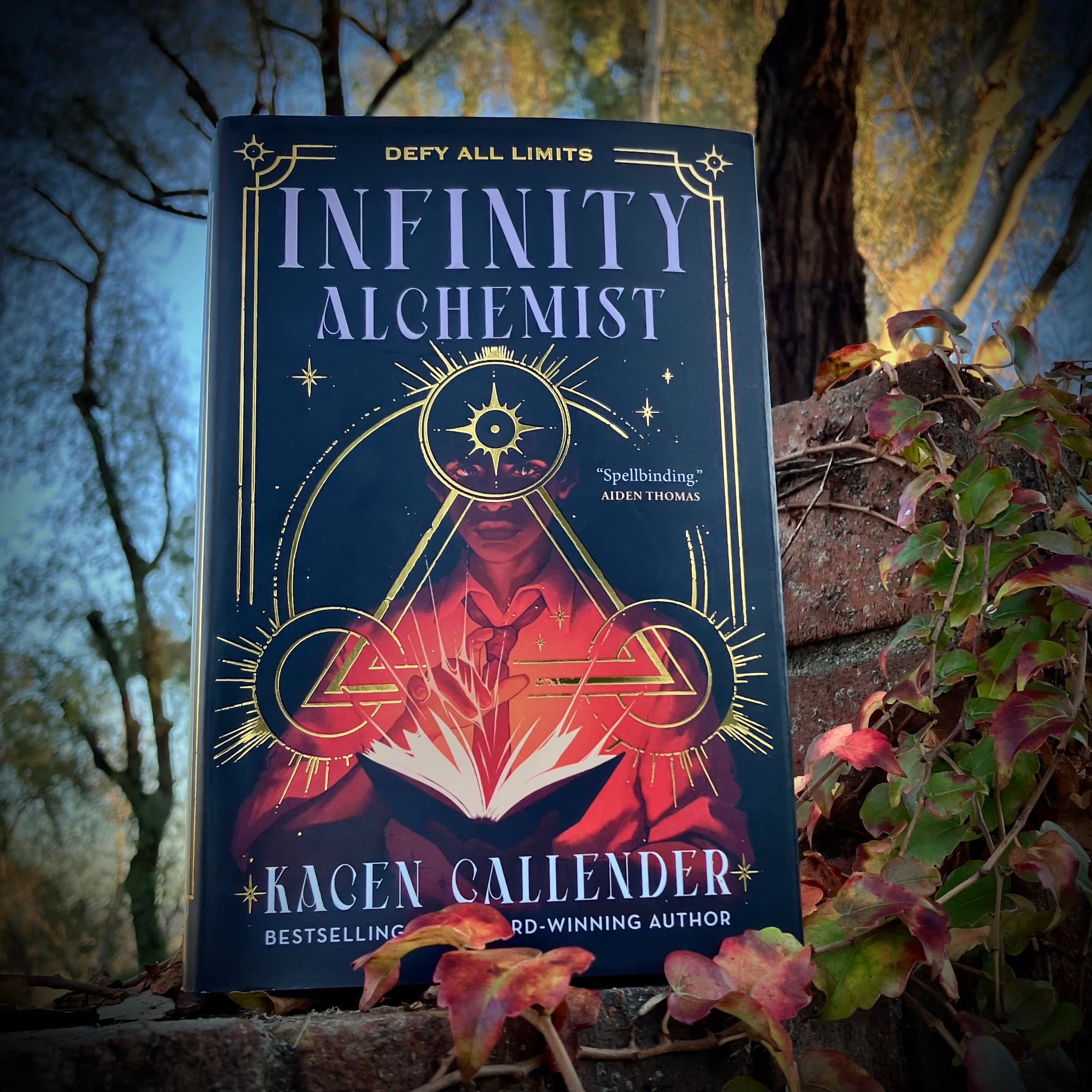

Bienvenidos a Cosplay Corner, where A-M dresses up as a book character or book cover!

A-M: For the first solstice edition of The Eavesdrop, I’m here with a tribute to Kacen Callender’s unforgettable fantasy novel Infinity Alchemist. Specifically, the character Ramsay Thorne, who got me right in my bigender heart.

This look was all about highlight, especially when it came to bringing out the definition of my brow bone and contouring my chin and jawline.

(I was also literally cutting my own hair in the half hour before I donned my Ramsay Thorne ensemble. Such is my commitment to cosplay and the level of Kacen Callender fanboy I am.)

To finish the makeup look, I thickened my eyebrows a bit, added black eyeliner, and used a neutral-ish peach lip color. But as much fun as I had with the makeup, it was getting into the outfit that really helped me get into character.

“Does your gender change often?” Ash had asked. He’d been about to leave, hand on the knob of her office.

Ramsay had given him an odd look. It wasn’t rude, per se, to ask about a person’s shifting gender—but it wasn’t a common topic of conversation.

“Maybe about once a day or so.”

The paperback edition of Sara's Mountain Upside Down is out February 10, 2026; a queer coming-of-age story that doesn't center coming out, a story with a fat protagonist that doesn't center on her body, and a library story that doesn't center book bans. (What does it center? Preorder and find out!)

Anica's Girl Reflected in Knife a modern fractured fairy tale about a heartbroken teen who tells a desperate lie and starts to lose track of her own truth, comes out in hardcover, ebook, and audio on April 7, 2026. Preorders deeply appreciated!

A-M's We Could Be Anyone, in which two teen con artists try to run an almost impossible scam at an exclusive Golden Age Hollywood resort, comes out (all queer puns intended) on May 26, 2026. Preorders very welcome!

Emily and Nova are hosting a working retreat through the Highlights Foundation / Retreat Center at Boyds Mills, and it is open to any (pre-published or published) writers who are in the messy middles of their YA and MG novels! We’ll chat about craft, offer writing prompts and Q&As, and allow ample time for actual writing. The retreat runs June 11-14. Sign up for one of the remaining spots now!

We shared a taste from Steering the Craft, and now we want to share the whole book with one of you! All subscribers are entered in the giveaway!

The winner will be randomly selected at the end of January, so subscribe now to be entered to win!